The Fine Art of Photography

It’s been at least twenty years since photography was accepted into the inner sanctum of the fine arts. But that hasn’t stopped photographers from quarreling among themselves over what makes a legitimate art photo

Charles Baudelaire: saw photography as a mechanical process not unlike “shorthand or printing”

Ultimately, photography prevailed. Today, most of the world's major fine-art museums routinely collect and exhibit photography. A 1904 Edward Steichen print of "The Pond-Moonlight" sold at Sotheby's in 2006 for almost $3 million. Works by other 20th century photographers including Richard Prince, Man Ray, and Edward Weston have all changed hands for prices in excess of $1 million.

True, these sums pale in comparison to a Matisse or Van Gogh. But consider that Steichen made 35 prints of "The Pond-Moonlight." Imagine if Van Gogh had painted 35 copies of "Still Life: Vase with Fifteen Sunflowers?"

Traditional fine-arts enjoy a mystique that has eluded photography for most of its history. "To many people, photography has seemed to be merely a reproductive medium," says Tad Beckman, a humanities professor and photography teacher at Harvey Mudd College. Or as Baudelaire put it, photography was closer to “shorthand or printing” than to a fine art.

American Pictorial Photography showing at the National Arts Club in NYC (1902)

Then, in 1888, the snap-shot was born with the introduction of the Kodak box camera and its U.S. advertising slogan: "You Press the Button, We do the rest!" Within a few years, box-camera carrying tourists -- known as “Kodakers” -- had fanned out across United States and Europe. Even if the fin-de-siecle art community had been inclined to reassess its position toward photography -- and there's no evidence that it was -- the advent of mass photography with its "press the button" mentality was taken as a vivid confirmation of Baudelaire’s ”mechanical” allegations.

When photography finally did enter the pantheon of fine arts about 100 years later, it was due to changing attitudes within the art establishment -- especially the advent of a Postmodern sensibility. Beginning in the late 1970s, the art-buying public began to collect photography. Then, in the 1980s, as Michael Langford, photography course director at the Royal College of Art in London, points out, “photography as a creative medium grew increasingly at home with other forms of fine art -- particularly printmaking and painting. In fact, it started to become difficult to see where one activity ended and the other began, since painters added photographic images to canvases and photographers abraded and handworked prints on photographic paper.”

What’s more, art dealers, critics, curators and collectors who had come of age during the creative ferment of the 1960s were taking charge of a vastly expanded fine-arts community. Performance art, installation art, even video art were suddenly the rage.

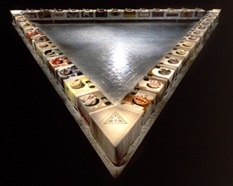

Judy Chicago: “The Dinner Party” (1976)

Except it isn’t.

The Great Rift

Henry Peach Robinson: “Fading Away” (1858). Robinson perfected composite printing to overcome the limitations of slow films and lenses

The dispute has deep roots. From the mid-19th century until the early 1930s, Pictorialism was the dominant movement in art photography and Henry Peach Robinson was its most influential advocate. Robinson had trained in oil painting at Britain’s Royal Academy of Art and was a devotee of J.M.W. Turner, whose moody, atmospheric paintings laid the foundation for impressionism.

Dr. Peter Henry Emerson: “The Old Order and the New” (1888)

Naturalism, however, differed from Straight photography as it would come be articulated during the 1920s in one significant respect. Emerson contended that human eye did not perceive everything within its field of vision in focus, so neither should the photograph appear entirely sharp. “Nothing in nature has a hard outline, but everything is seen against something else, and its outlines fade gently into something else,” he argued. But deliberately blurring parts of an image was a novel, and not entirely welcome, idea at a time when photographers were devoted to overcoming the limitations of extremely slow lenses and light-sensitive materials.

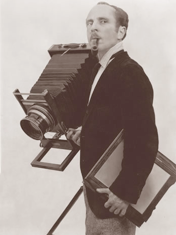

Edward Weston: pictorialist to purist

As with many expressive pursuits, Pictorialism was, almost by definition, prone to excess. While the Naturalist movement was generally content to let the photograph “speak for itself,” Pictorialists wanted to make images that conveyed messages, meanings and emotions. This was a lofty ambition. And when it didn’t work out, there was a long way to fall.

In the 1920s, the concept of artistic Purism began to exert a strong influence on American painting, sculpture and photography. Purists held that each artistic medium has its own distinctive and compelling properties, that art should stress harmony, logic and mathematical order without fantasy or individual expression. In embracing Purism during the 1920s, photographer Paul Strand launched the first salvo in what would become an all out war on expressive photography: “If photographers let other people’s vision get between the world and their own, they will achieve that extremely common and worthless thing, a Pictorial photograph.” By the early 1930s, Straight photography based on Purist concepts had gained important adherents on both the U.S. East and West coasts, including Weston and Steichen, who disavowed their former Pictorial style for a new hard-edged realism.

Straight photography valued sharpness, tonality and photographic “authenticity.” Its supporters did not necessarily reject image manipulation -- as long as the result “looked photographic.” But they believed that photography should always maintain an intimate link between image and reality, and that it is the quality of light reflected by an object or scene lends the photographic image its unique power.

Imogen Cunningham: “Portrait of Frida Kahlo” (1932)

But its advocates were also inclined to treat Straight photography as a moral crusade. "While Straight photography clearly won the day in 1932, nowadays it is the dogmatic Purism of that camp that seems most dated," says Richard Nilsen, an art critic for The Arizona Republic. The vanguard of the Straight photography movement had an agenda that went far beyond establishing Purism’s dominance. The goal was nothing less than erasing the memory of Pictorialism altogether. And they were surprisingly successful.

Ironically, the cruelest blow was not delivered by Purism’s vocal, manifesto-writing partisans, but rather a pair of soft-spoken academics named Nancy and Beaumont Newhall. In the mid-1930s, as librarian for the recently founded Museum of Modern Art (MOMA) in New York, Beaumont Newhall recognized the need for an authoritative history of photography. In 1949, MOMA published Nancy and Beaumont Newhall’s The History of Photography which went on to become a standard textbook in art and photography courses as well as the starting point for subsequent works like Naomi Rosenblum’s 1984 A World History of Photography.

Man Ray: “A l'heure de l'observatoire - Les amoureux,” circa 1930s

This may sound like an arcane academic dustup. But imagine a history of American politics that barely mentions the Democratic party? The Beaumonts censored and twisted their historical research to justify, legitimize and aggrandize a specific photographic style. In so doing, their work explicitly benefited the reputations and finances of a small group of their closest friends and professional associates.

Jerry Uelsmann: from Modern to Postmodern

The Postmodern Era

Beginning in the 1960s, photography was overtaken by the same wave of activism, rebellion and experimentation that swept across the U.S. and European social and cultural landscape. "Creative freedom" became a mantra endlessly repeated in both the editorial and advertsing pages of the photographic press. Even as some of its acolytes were attaining the status of cultural icons, Straight photography itself was surrendering to a rising tide of automated cameras, accessories and self-trained photographers. By the mid-70s, critic Susan Sontag could declare that "recently, photography has become almost as widely practiced an amusement as sex and dancing." The idea of photography as self-expression was back with a vengeance.

In the vernacular of art criticism, the 60s marked the emergence of Postmodern photography. During the 60s, art photography was swept up by the same vast sea change that was transforming Western culture at large. In addition, the relatively inexpensive and easily mastered SLR -- notably the 1959 Nikon F, the 1964 Pentax Spotmatic, and the 1971 Canon F1 -- attracted millions of aspiring “creative” photographers who were oblivious to the dictates or even the existence of photographic Purism. Others, however, were as much in open revolt against Straight photography as the Purists had been in rebellion against Pictorialism. UCLA printmaker Robert Heinecken, for instance, emerged as the spokesmen for a West coast group that, in effect, declared that: ‘Photographers who limit their vision to a purely objective representation of reality will achieve that extremely common and worthless thing, a Straight photograph.’

Creative Freedom: Broadway poster for “Hair” with a solarized photo and Rastafarian color scheme reflects the 60s art and social revolution

One convenient moment by which to mark the transition between Modern and Postmodern photography is Uelsmann’s 1966 speech before a Society for Photographic Education conference in Chicago where he used Purist language to argue for a Pictorialist idea: “Let us not be afraid to allow for ‘post-visualization.’ By post-visualization I refer to the willingness on the part of the photographer to re-visualize the final image at any point in the entire photographic process.” In other words, photographers should not be afraid to approach photographic image making in ways that had been stigmatized by the Purists for more than three decades.

Haleh Bryan: “Tears and Shadows” 2004

When it comes to photographic styles, the larger art world remains steadfastly agnostic. Pictorial and Purist images have both commanded six-figure sums at auction. If anything, art historians and curators like to think of photography as a succession of movements -- Pictorialism, Photo-secession, Surrealism, Modernism, Straight/Purist, Constructivism, Postmodermism, etc. -- an approach that simplifies the work of cataloguing collections and providing narrative context for exhibitions. Among photographers, however, the issue of style can still incite passionate -- even hostile -- disagreement.

László Moholy-Nagy: “Photogram” (1923)

"Postmodern photography has no problem in manipulating images, just like the Pictorialists did," says The Arizona Republic's Nilsen. "Indeed, it revels in mucking around in digital software, in setting up artificial tableaux, in creating counterfactual icons and basically thumbing its nose at the idea that there could be such a thing as Straight photography in the first place." Whether the intention is nose thumbing or not, almost anyone who "mucks around in digital software" soon discovers that there is a small but strident group that is offended by the very idea of the digitally-elaborated photograph.

From the Purist perspective, it’s almost as if digital editing has brought photography full circle -- back to the bad old days when Pictorialism dominated and wannabe painters posed as art photographers. But this is hardly the 1920s.

Diane Arbus: “Albino Sword Swallower” (1971)

Ironically, it was the repudiation of the philosophy of Straight photography, which by the late 1960s was becoming increasing irrelevant, that helped establish the medium’s fine-art "cred." Today, photography is in a new era that abounds with fresh possibilities. After all, photography is, at heart, a technology -- and a rapidly evolving one, at that. Had art photography been confined by Purist dogma, much of the most dynamic and intellectually challenging work of the past half century or so would not exist. There would be no Herbert Bayer or Man Ray, no László Moholy-Nagy or Jerry Uelsmann, and perhaps not even a Cartier-Bresson or Diane Arbus.

All of which makes angry rejection of other approaches by Straight photography's remaining adherents seem self-righteous and, ultimately, self-serving. Man Ray summed up the issue neatly when he wrote during the 1930s that:

In the same spirit, when the automobile arrived, there were those that declared the horse to be the most perfect form of locomotion. All these attitudes result from a fear that the one will replace the other. Nothing of the kind happened. We have simply increased our range, our vocabulary. I see no one trying to abolish the automobile because we have the airplane."

Photography would do well to leave this philosophical squabble behind and get on with the business of making art. Can't we just accept that like every other form of fine art, the photographic image can be objective and representational, or subjective and expressive, or even a little of both?

Unfortunately, the answer seems to be ‘No!’ Straight photography is a belief system that, like religion, requires commitment, discipline and sacrifice to uphold. It teaches ‘our way is the only way.’ Photography, however, has become a banquet with enough variety for almost any palate. Purists, who only allow themselves bread and cheese, have grown resentful of the other diners. The more diverse and tempting the banquet becomes, the deeper the grudge.

Visceral Reactions

Even so, the works that incite my deepest, most "visceral reactions" are usually subjective. Laszlo Moholy-Nagy's photograms, Paul Caponigro's abstractions and Jerry Uelsmann's elegant, dream-like photo composites all had this kind of physical impact when I first encountered them in the 1970s -- and they continue to move and inspire me several decades later. Yes, there can be subtle beauty in a great landscape photo, or important historical lessons to be gleaned from good photojournalism, but for me it is the subjective perspective that spins a seductive web of ineluctable mystery.

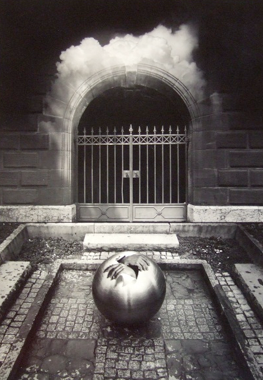

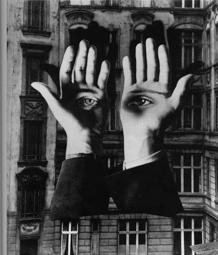

Herbert Bayer: “The Lonely Metropolitan” 1932

Which brings us to the emotionally-charged issue of photographic image manipulation.

Jim McNitt: “She Moaned” (1994) digitally ‘elaborated’ and composited photo

Lens selection, composition, f-stop and shutter-speed combinations, filters, etc. are all subtle forms of in-camera manipulation. Dodging, burning, contrast filters and chemical processing are all forms of darkroom manipulation. Some of the best known straight-photography American landscapes involved printing from multiple negatives -- as well as enough chemical processing and reprocessing to start a small toxic waste dump.

Ben Goosens: “Rain and Snow,” 2007

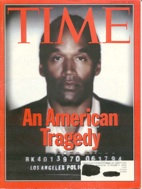

There should be zero tolerance for manipulation is photojournalism. After spectacular gaffes by Time and National Geographic, among others, news organizations have adopted such rigid standards that a press photographer like Weegee, who was known to sometimes stage scenes for maximum visual impact, would be summarily fired today.

Magie Taylor: “Garden,” 2005

Straight photography and photojournalism are well suited for revealing the objective "truth of the moment." But, if nothing else, Postmodernism has shown that photography can also penetrate the uncharted territory where truth speaks not so much with the bright light of clear reason, but in the shadowy and inchoate voice of dreams and fantasies. We are still in the infancy of our understanding this other, subjective realm. In the hands of inquisitive and creative artists, digital tools are helping define a new grammar, a new language and perhaps even a new understanding, or at least an increased familiarity with the inner realms of human experience. "Just as the technology of the 1860s defined photographic truth in that era, so now are digitalization and the Internet redefining how we know the twenty-first century," says Hirsch. "We seem to be coming full circle, giving image makers authority to again explore their subject with subjectivity both in and after the moment of witnessing."

Guilty: Time’s manipulated mug shot, 1994

It is, at best, an irrelevant and unproductive discussion because, as far as the rest of the art world is concerned, Straight photography and Pictorial photography were no more than two historic movements within the same medium. Neither one is inherently more deserving to called fine art than the other. "Art photography is anything that you frame and put on the wall," according to one common photographer’s quip. "Whether it is fine or not is up to the viewer."

--Jim McNitt November, 2007

Principal Works Consulted

Coleman, A.D., "The Perils of Pluralism: Thoughts on the Condition of Photography at Century's End," 1999, www.detroitfocus.org/CurrentFocus/Portfolio/Extras/ADColeman.html (Nov. 15, 2007)

Coleman, A.D., Depth of Field, University of New Mexico Press, 1998

Hirsch, Robert and Greg Erf, "Perceiving Photographic Truth,” http://lightresearch.net/articles/photographictruth.html (Nov. 15, 2007)

Hirsch, Robert and Greg Erf, "Truth of the Moment & Truth of Reflection," http://lightresearch.net/articles/reflection.html (Nov. 15, 2007)

Hirsch, Robert, "Flexible Images: Handmade American Photography,

1969 – 2002," 2003, http://lightresearch.net/articles/handmade.html (Nov. 15, 2007)

Leggat, Robert, "A History of Photography," 1995, www.rleggat.com/photohistory (Nov. 15, 2007)

Langford, Michael, The Story of Photography, Focal Press, 1997.

Neilsen, Richard, "Old Photography Debate Renewed," The Arizona Republic, Oct. 8, 2007, http://www.azcentral.com/ent/arts/articles/1008f64.html (Nov. 17, 2007)

Nickel, Douglas R., "History of Photography: The State of Research," The Art Bulletin, 2001. http://www.encyclopedia.com/doc/1G1-84192649.html (Nov. 15, 2007)

Newhill, Beaumont and Nancy, The History of Photography, Bulfinch,1982

Rosenblum, Naomi, A World History of Photography, Abbeville Press, 1997

Sontag, Susan, On Photography, Picador, 2001